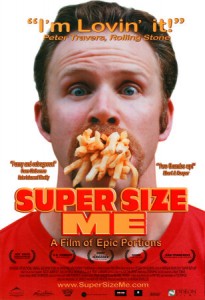

This weekend, I saw Morgan Spurlock’s “Super Size Me”. The up-and-coming filmmaker has been compared to Michael Moore, but offers a more urban point of view. It’s not a film for the faint of stomach — at one point, there’s a stomach-stapling surgery procedure, and many collages of overweight Americans, mostly from Texas (where 5 of the top 10 overweight cities in the U.S. reside). The film, according to today’s Wall Street Journal, has grossed about $4.3 million, far behind the weekend takes of both Shrek 2 ($92.2m) and The Day After Tomorrow ($86.6m), but a great start for a documentary. The buzz generated from the film has allowed it national exposure, and Spurlock has handled himself well on camera, defending critics of the film (fast food restaurants and associations, of course) and presenting lucid arguments (his 30-day McDonald’s diet, at 5,100 calories a day, is actually quite normal for a sizeable portion of our population — consider the Egg McMuffin for breakfast, Wendy’s for lunch, and a Pizza for dinner).

This weekend, I saw Morgan Spurlock’s “Super Size Me”. The up-and-coming filmmaker has been compared to Michael Moore, but offers a more urban point of view. It’s not a film for the faint of stomach — at one point, there’s a stomach-stapling surgery procedure, and many collages of overweight Americans, mostly from Texas (where 5 of the top 10 overweight cities in the U.S. reside). The film, according to today’s Wall Street Journal, has grossed about $4.3 million, far behind the weekend takes of both Shrek 2 ($92.2m) and The Day After Tomorrow ($86.6m), but a great start for a documentary. The buzz generated from the film has allowed it national exposure, and Spurlock has handled himself well on camera, defending critics of the film (fast food restaurants and associations, of course) and presenting lucid arguments (his 30-day McDonald’s diet, at 5,100 calories a day, is actually quite normal for a sizeable portion of our population — consider the Egg McMuffin for breakfast, Wendy’s for lunch, and a Pizza for dinner).

As I’m watching the film, I’m wondering how many people in the room are part of the audience Spurlock was refers to. I’m in Seattle, a quite health-conscious city, and when the lights go up at the end of the film, I see two people in the theatre with super-sized frames holding super-sized beverages, and I begin to wonder if I would start judging people with that physique for making poor personal diet choices or being the victims of an onslaught of advertising and marketing they’ve experienced since childhood.

On childhood, a segment of the film talks about the current state of the US school lunch program. I was in high school during the late 80s, and while we had institutional pizza, fries, cheeseburgers and other partially-hydrogenated vegetable oil delicacies, there was also an option for a salad bar, where, if you didn’t submerge the lettuce with dressing, there was a chance you’d leave the grounds with some nutritional value. When the state insitutionalizes these high-salt, high-fat products (engrained extensively through school and fast food chain partnerships), they’re giving students the idea that these foods are (part of) a healthy diet, and one can’t help but think of the connection between the Standard American Diet (SAD) and the explosion in diabetes- and heart-related illnesses.

I can’t be one to judge, though. I have a weakness for Taco Bell once in a great while, usually preceded by a few beers earlier in the evening. The 7-layer burrito, bean burrito and an order of mexi-nuggets (read: tater tots with spices) have kept me from a headache the next day.

In addition to reading “Diet for a New America” by John Robbins, and other media of the genre, I leave “Super Size Me” profoundly aware of the damage these foods offer America, and I think about the marketing of foods, the graphics, the excessive packaging, the marketing towards children, and wonder why Congress hasn’t classified these foods as Weapons of Mass Destruction, since food-related illness is the second leading cause of death (right behind smoking) in America.

But I know there’s hope. The organic food industry is experiencing exponential growth (given officlal recognition by the USDA’s Organic food labeling system), and organic, healthy products appear in mainstream grocery stores (only an aisle or two per store, but it’s a start). Non-profits, like the Organic Consumers Association are making sure government holds steady to organic standards (with a recent victory preventing the watering down of these standards) and going after major offenders like Monsanto (a good start for charter revocation, and that wisely decided not to commercialize a genetically-modified wheat, due to lack of demand, trust in the product, and export worries).

There’s still a long way to go. The USDA will need to stand up to the food lobbies and present dietary guidelines that matter. School boards need to allow alternatives to existing school lunch programs, and receive funding for these options (a minimal price difference). Congress will need to toughen guidelines for advertising fast and processed foods (similar to the Surgeon General’s warning for cigarettes, with the addition of banning ads during child-specific television programs). Of course, personal responsibility plays a strong role, too. Most of us know that these foods are bad for us, but we eat them anyway. As tobacco lawsuits were for the 90s, this decade promises to be the way we feed our children.

Share on Facebook